Data model

The data model is a fundamental part of any Genesis application. To create a data model, you define the entities (tables) that store the application's data. Each entity (table) consists of one or more attributes (fields) that contain the data.

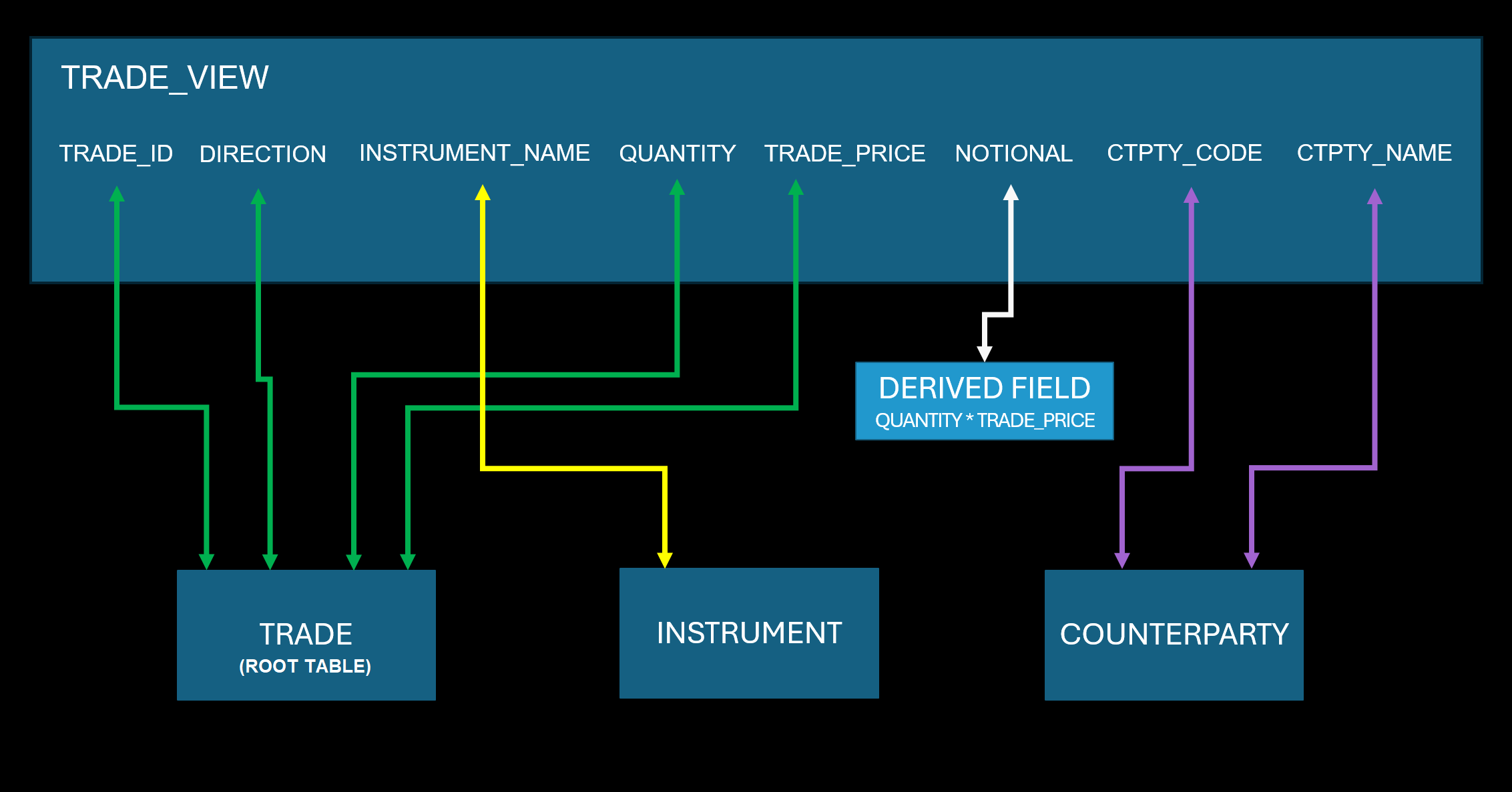

You also define views, which join related entities together to provide useful views of the data. For example, it makes sense to have separate tables for counterparties, instruments and exchanges, but if you want to look at the trades or the orders in the system, you probably want to see some or all of the fields from these different tables in a single grid of data for each trade or order you make. For this, you need a view.

The application's tables and views enable the platform to notify Genesis Server and Client services and components automatically whenever there are changes to the data in the table or view they are using.

The data model of a Genesis Application is defined in *-dictionary.kts files.

Example configuration

Tables

Each table is defined with a set of fields (entity attributes), which make up a record representing the entity.

Each table requires:

- a unique name and unique id

- one or more fields (attributes)

- one primary key

Example data model

Below is an example -tables.dictionary.kts configuration. It defines three tables: TRADE, COUNTERPARTY and INSTRUMENT

tables {

table(name = "TRADE", id = 11_000, audit = details(id = 11_500, sequence = "TA")) {

field("TRADE_ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

field("COUNTERPARTY_ID", LONG).notNull()

field("DATE", DATE).notNull()

field("DIRECTION", ENUM("SELL","SHORT_SELL","BUY")).default("BUY")

field("INSTRUMENT_ID", LONG).notNull()

field("QUANTITY", INT).notNull()

field("TRADE_PRICE", DOUBLE).notNull()

primaryKey("TRADE_ID")

indices {

nonUnique("COUNTERPARTY_ID").name("TRADE_BY_COUNTERPARTY_ID")

nonUnique("INSTRUMENT_ID").name("TRADE_BY_INSTRUMENT_ID")

nonUnique("DATE").name("TRADE_BY_DATE")

nonUnique("COUNTERPARTY_ID", "DATE").name("TRADE_BY_CPTY_DATE")

}

}

table(name = "INSTRUMENT", id = 11_001) {

field("INSTRUMENT_ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

field("NAME", STRING(100)).notNull().metadata {

maxLength = 100

}

primaryKey("INSTRUMENT_ID")

}

table(name = "COUNTERPARTY", id = 11_002) {

field("COUNTERPARTY_ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

field("COUNTERPARTY_CODE", STRING(100)).notNull().metadata {

maxLength = 100

}

field("NAME", STRING(100)).notNull().metadata {

maxLength = 100

}

primaryKey("COUNTERPARTY_ID")

}

}

Views

To create a view, you must start with a "root" table, the main table powering the view. You then define tables that join to it - or to any other table already joined in the view - in order to make up the view.

Below is a view called TRADE_VIEW, based on the example table configuration above. It defines the TRADE tables as its root, and it joins to two further tables (INSTRUMENT and COUNTERPARTY) to create the view.

Views can also contain derived fields. These are fields with values derived from one or more other fields in the view. In the example above, you can see NOTIONAL which is the product of QUANTITY and TRADE_PRICE.

The example above can be configured as follows:

views {

view("TRADE_VIEW", TRADE) {

joins {

joining(INSTRUMENT, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(TRADE { INSTRUMENT_ID } to INSTRUMENT { INSTRUMENT_ID })

}

joining(COUNTERPARTY) {

on(TRADE { COUNTERPARTY_ID } to INSTRUMENT { COUNTERPARTY_ID })

}

}

fields {

TRADE.allFields()

INSTRUMENT.NAME withPrefix INSTRUMENT

COUNTERPARTY.COUNTERPARTY_ID

COUNTERPARTY.COUNTERPARTY_CODE withAlias CTPTY_CODE

COUNTERPARTY.NAME withAlias CTPTY_NAME

derivedField("NOTIONAL", DOUBLE) {

withInput(TRADE.QUANTITY, TRADE.PRICE) { quantity, price ->

quantity * price

}

}

}

}

}

You can also store and reuse the derived field withInput calculations, like so:

views {

view("TRADE_VIEW", TRADE) {

joins {

joining(INSTRUMENT, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(TRADE { INSTRUMENT_ID } to INSTRUMENT { INSTRUMENT_ID })

}

joining(COUNTERPARTY) {

on(TRADE { COUNTERPARTY_ID } to INSTRUMENT { COUNTERPARTY_ID })

}

}

fields {

TRADE.allFields()

INSTRUMENT.NAME withPrefix INSTRUMENT

COUNTERPARTY.COUNTERPARTY_ID

COUNTERPARTY.COUNTERPARTY_CODE withAlias CTPTY_CODE

COUNTERPARTY.NAME withAlias CTPTY_NAME

val myLambda: DerivedField2<Double, Double, Double> = { quantity, price -> quantity * price }

derivedField("NOTIONAL", DOUBLE) {

withInput(TRADE.QUANTITY, TRADE.PRICE, myLambda)

}

}

}

}

Summary

Tables and views of data can be used to power client queries, both snapshot and real-time, which in turn can power grids, charts and client components that rely on data.

Tables and views are also used to power server capabilities, such as:

- real-time aggregation

- real-time triggers

- outbound integrations

Configuration options

table

Tables and their fields are defined in *-tables-dictionary.kts files. These files are placed in the cfg folder in your application's server codebase.

| Parameter name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

name | String | name of the table, must be unique across the application |

sequence | String | Unique characters for the sequence ID on the audit table |

audit | details | See below |

Audited tables

audit can optionally be defined to make the table auditable

It is a common compliance requirement that a system audits all changes to critical system records.

The following details can be added when you use the audit = details() parameter:

| Parameter name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

id | Integer | Unique id for the audit table |

sequence | String | Unique characters for the sequence ID on the audit table |

tsKey | Boolean | Set a timestamp index (defaulted to false where not specified) on the audit table. The index name will be <source-table>_AUDIT_BY_TIMESTAMP |

The audit table that is created has the same name as the source table, plus the suffix _AUDIT. Here is an example table definition, for a table TRADE which will have a TRADE_AUDIT table automatically generated to store audit records.

table(name = "TRADE", id = 11_000, audit = details(id = 11_500, sequence = "TA")) {

field("TRADE_ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

...

}

Structure of audit tables

When you create an audit table, it has all the same fields as the source table, plus the following fields:

| Field name | Data Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

AUDIT_EVENT_DATETIME | DATETIME | Autogenerated date and time of the event |

AUDIT_EVENT_TEXT | STRING | Optional REASON value sent as part of the event message |

AUDIT_EVENT_TYPE | STRING | The event that wrote on the source table |

AUDIT_EVENT_USER | STRING | User on the event message |

<source-table>_AUDIT_ID | STRING | A generated unique ID for the audit record, which uses the sequence defined in the audit = details() detailed above, where <source-table> is the name of the table being audited. |

field

A table is made up of one or more fields. Each field must have a unique name (unique within the table definition) and a data type.

When you are defining a field, there is a range of data types available. These are described in the sections below.

String

String fields can contain any set of characters up to the maximum length of characters specified for the field.

In the second example below, the value in the parenthesis is the maximum number of characters that can be stored in this field for a given record. If you do not specify this value, the default length is 64 characters.

Now look at the third example. Different database technologies have different limits. So you can use dbMaxSize to set the field length to the maximum allowed for the database technology used by the application.

Example definitions

field("MY_STRING", STRING)

field("MY_STRING", STRING(256))

field("MY_STRING", STRING(dbMaxSize))

Enum

Enum (aka enumerated) fields specify the exact set of values which the field can be set to. They are helpful when you have a definitive set of values and want to present users with a pick-list.

You can specify an alias for each value of the enum using the keyword to. This enables you to create a human-readable representation of the value. The second example below shows an enum with three possible values, each of which has a longer alias.

By definition, an enum must have a default value. Where no default is specified, the first value in the list is set as the default. So, in the first two examples below, the default for MY_ENUM is B. However, you can set the default explicitly; in the third example, the default for MY_ENUM is set to S.

Example definitions

field("MY_ENUM", ENUM("B", "S", "SS"))

field("MY_ENUM", ENUM("B" to "Buy", "S" to "Sell", "SS" to "Short Sell"))

field("MY_ENUM", ENUM("B", "S", "SS")).default("S")

Boolean

Boolean fields must contain a value of either true or false.

Example definition

field("MY_BOOLEAN", BOOLEAN)

Date

Date fields must contain a value representing a date. Dates represent a day in time, they do not include time precision.

Example definition

field("MY_DATE", DATE)

Datetime

Datetime fields must contain a value representing a point in date and time.

Example definition

field("MY_DATETIME", DATETIME)

Integer

Integer (aka Int) fields represent whole numbers, with no decimal places. Integers can only hold 32 bits, and the maximum value is just over 2.14 billion. If you need larger numbers, use the type Long.

Example definition

field("MY_INT", INT)

Long

Long fields are similar to integer, but represented in 64 bits. This means it has a much larger maximum value. Longs are used a lot for auto-generated primary keys so that you can theoretically store many more records.

Example definition

field("MY_LONG", LONG)

Short

Short fields can store whole numbers from -32,768 to 32,767. They are very rarely used, but are useful if the data needs to be stored in memory more efficiently.

Example definition

field("MY_SHORT", SHORT)

Double

Double fields are used to store numeric values with decimal places.

Double values can lose precision for large numbers, or numbers with many digits to the right of the decimal place. If you need to keep this precision, use BigDecimal.

Example definition

field("MY_DOUBLE", DOUBLE)

BigDecimal

Big Decimal fields store numeric values with decimal places. They enable you to define the precision and scale to ensure that values are always accurate for the use case. The second example below sets the precision to 10 and scale (the number of decimal places) to 3.

- Precision is the number of digits in the number (default where not specified is 20)

- Scale is the number of digits to the right of the decimal point (default where not specified is 5)

Example definitions

field("MY_BIGDECIMAL", BIGDECIMAL)

field("MY_BIGDECIMAL", BIGDECIMAL(10, 3))

Nano Timestamp

A nano timestamp is a precise way to record a timestamp to the closest nano seconds.

Example definition

field("MY_NANO_TIMESTAMP", NANO_TIMESTAMP)

Raw

Raw fields are intended to store large values. They can contain:

- large structured payloads

- binary data

- other non human readable data

Example definition

field("MY_RAW", RAW)

Fields can also have metadata defined to give them additional characteristics

autoIncrement

Only valid for fields of type LONG

This setting will ensure a long number, starting from 1, will be auto-generated. It will increment for each record added.

field("ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

sequence

You can use sequence to auto-generate a sequential number followed by a 2-character reference.

The numeric part of the value will be incremented for each record added. The complete value is padded as follows: SEQUENTIAL_VALUE (padded by paddingSize) + SEQUENCE + LOCATION + 1.

sequence is only valid for fields of type STRING.

The syntax is field("ID", STRING).sequence("AA")

Example definition

field("TRADE_ID", STRING).sequence("TR")

In this example, where the application has system definition Location set to NY, the generated values will be 000000000000001TRNY1, then 000000000000002TRNY1, and so on...

If your application is set to use an SQL database, then you must make the following changes to your system definition.

item(name = "SqlSequencePaddingSize", value = 15)

item(name = "SqlEnableSequenceGeneration", value = true)

If you do not make these settings and you are using an SQL database, then sequence will generate a uuid by default.

uuid

A uuid is a Universally Unique Identifier; it is a randomly generated string, which is not sequenced, but which guarantees that a unique value is generated.

field("TRADE_ID", STRING).uuid()

default

This specifies a default value for the field. If no value is set for the field before writing the record to the database, then the field is set to the default value you have specified here.

Add .default(<value>) to your field definition to set a default. The value must be valid for the data type of the field.

Valid for types

any

Example definition

field("IS_CORRECT", BOOLEAN).default(true)

notNull

This marks a field as mandatory. If you specify notNull, then a value MUST be set for this field on every record. Where the field value is not set for a given record, the database API will reject the record.

Where this is not set for a field, its values can be left as null - unless it is part of the primary key or any index on the table. A field set with a default value can never be null.

Valid for types

any

Example definition

field("MY_BOOLEAN", BOOLEAN).default(false)

sensitive

String fields can be marked as sensitive(). Use this when the value needs to store keys, passwords or other sensitive data. Values will be masked when printed to console or logs, or when toString() is used in conjunction with the field on a database API.

Valid for types

STRING

Example definition

field("KEY", STRING).sensitive()

min

Use min to specify a minimum value for a field. The platform will validate any value input to the field. If the value is not greater than or equal to the value you have specified, it will be rejected by the DB layer.

You specify the value as metadata, as shown in the example definition.

Valid for types

Any numeric types except BigDecimal

Example definition

field("RATING", INT).metadata {

min = 0

}

max

Use max to specify a maximum value for a field. The platform will validate any value input to the field. If the value is not less than or equal to the value you have specified, it will be rejected by the DB layer.

You specify the value as metadata, as shown in the example definition.

Valid for types

Any numeric types except BigDecimal

Example definition

field("RATING", INT).metadata {

max = 10

}

minLength

Use minLength to specify a minimum length for a value in a field. The platform will validate any value input to the field. If the value is less than the value you have specified, it will be rejected by the DB layer.

You specify the value as metadata, as shown in the example definition.

Valid for types

STRING

Example definitions

field("ISIN").metadata {

minLength = 12

}

maxLength

Use maxLength to specify a maximum length for a value in a field. The platform will validate any value input to the field. If the value is greater than or equal to the value you have specified, it will be rejected by the DB layer.

You specify the value as metadata, as shown in the example definition.

Valid for types

STRING

Example definitions

field("ISIN").metadata {

maxLength = 14

}

pattern

Use pattern to set a regular expression pattern that values must adhere to. This could be the format of a postal code or an instrument code, for example.

You specify the value as metadata, as shown in the example definition. The platform will validate any value input to the field. If the value does not match the pattern you have specified, it will be rejected by the DB layer.

Valid for types

STRING

Example definition

field("ISIN").metadata {

pattern = "^[A-Z]{2}[-]{0,1}[A-Z0-9]{9}[-]{0,1}[0-9]{1}$"

}

title

Use title to give the field a name. Typically, this is used to provide a more descriptive name when displaying the field in the front end of the application.

Every field has a default title (derived from the field name converted to title case, e.g. MY_STRING_FIELD becomes "My String Field"), but you can specify title(<title value>) to override this.

Valid for types

any

Example definition

field("KEY", STRING).title("Access key")

Event field modifiers

You can add modifiers for fields to cover scenarios such as:

- where the field is derived and should not be modified by the end user, only by the system itself

- where the field should only be set on insert, and never changed by modify events

You can set the following modifiers:

| Modifier | Valid Field Type | Effect |

|---|---|---|

.username() | STRING | The field value gets set to the username of the user submitting the event. |

.timestamp() | DATE | The field value is set to the current date. |

.timestamp() | DATETIME | The field value gets set to the current date and time. |

.readonly() | any | The field is available during insertion, but not on modification. |

.applicationProvided() | any | The field must be provided programmatically in the eventHandler. User input from the front end is not accepted. |

Once you have defined a field with one of these modifiers, then you don't need to specify any further logic in the relevant eventHandler to enforce the validation that you have specified.

If you use Genesis Create to create your client app, then the forms that are auto-generated for submitting to tables will automatically take this logic into account.

For example, if you have set the field to readonly() and you have an entity manager using the table as a data source, then the specified field will be available in the auto-generated Insert form but not in the auto-generated Modify form.

table(name = "TRADE", id = 11002) {

field("ID", INT).primaryKey().autoIncrement()

...

field("ENTERED_BY").username().readonly()

field("LAST_UPDATED_BY").username()

field("ENTERED_AT", DATETIME).timestamp().readonly()

field("LAST_UPDATED_AT", DATETIME).timestamp()

...

}

sharedField

You can use sharedField to define field definitions that can be reused across multiple tables. This is particularly useful for enum fields that represent the same set of values in different tables, ensuring consistency and reducing duplication.

Currently, the accepted shared fields are:

- Simple enums (e.g.,

ENUM("X", "Y", "Z")) - Aliased enums (e.g.,

ENUM("BUY" to "Buy Order", "SELL" to "Sell Order"))

When using a shared field, you can:

- Use it as-is with its original name

- Override the field name on a per-table basis

The default value of the ENUM in a shared field declaration will always be the equal to the first parameter.

Example definition

In a trading application, both TRADE and ORDER tables might need a DIRECTION field to indicate whether the trade or order is a buy or sell. Instead of defining the enum separately in each table, you can define it once as a shared field:

tables {

// Define the shared field once

val directionEnum = sharedField("DIRECTION", ENUM("SELL", "SHORT_SELL", "BUY"))

// Use the shared field in the TRADE table

table(name = "TRADE", id = 11_000) {

field("TRADE_ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

field("COUNTERPARTY_ID", LONG).notNull()

field("DATE", DATE).notNull()

field(directionEnum) // Uses the field name "DIRECTION"

field("INSTRUMENT_ID", LONG).notNull()

field("QUANTITY", INT).notNull()

field("TRADE_PRICE", DOUBLE).notNull()

primaryKey("TRADE_ID")

}

// Use the shared field in the ORDER table with the same name

table(name = "ORDER", id = 11_010) {

field("ORDER_ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

field("INSTRUMENT_ID", LONG).notNull()

field(directionEnum) // Also uses the field name "DIRECTION"

// ... other fields

primaryKey("ORDER_ID")

}

}

Using shared fields with aliased enums

You can also create shared fields with aliased enums:

tables {

// Shared field with aliased enum values

val directionEnum = sharedField(

"DIRECTION",

ENUM("BUY" to "Buy Order", "SELL" to "Sell Order", "SHORT_SELL" to "Short Sell")

)

table(name = "TRADE", id = 11_000) {

field("TRADE_ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

field(directionEnum)

// ... other fields

primaryKey("TRADE_ID")

}

}

Overriding the field name

You can override the field name when using a shared field in a specific table by providing a different name as the first parameter:

tables {

val directionEnum = sharedField("DIRECTION", ENUM("SELL", "SHORT_SELL", "BUY"))

table(name = "TRADE", id = 11_000) {

field("TRADE_ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

field(directionEnum) // Field name is "DIRECTION"

// ... other fields

primaryKey("TRADE_ID")

}

table(name = "ORDER", id = 11_010) {

field("ORDER_ID", LONG).autoIncrement()

field("ORDER_DIRECTION", directionEnum) // Field name is "ORDER_DIRECTION" instead

// ... other fields

primaryKey("ORDER_ID")

}

}

primaryKey

Every table must have a single primary key. You must set this to be one or more fields from the table. The values for the primary key fields must uniquely identify a record in the table.

There are two different ways to define a primary key:

- Set

.primaryKey()against a field defined in the table. e.g.field("ID", LONG).autoIncrement().primaryKey(). - Define

primaryKey(<field 1>, <field 2>, ...)within a table definition with one or more fields as inputs, for example:primaryKey("BOOK_ID", "INSTRUMENT_ID", "COUNTERPARTY_ID").

When defining a multi-field primary key, the order in which the fields are specified is important. Their precedence sets more efficient ways to look up ranges of records in the API. For example, in the definition above we could efficiently get a list of the entity for a given BOOK_ID, or for a given combination of BOOK_ID and INSTRUMENT_ID.

Fields marked as part of a primary key cannot be null.

By default, the platform automatically generates names for each key in the following format:

<TABLE_NAME>_BY_<FIELD_1>(+_<FIELD_N>).

If you wish to give your primary key a specific name, apply .name(<pk name>) against it. Here are two examples:

field("ID", LONG).autoIncrement().primaryKey().name("POSITION_BY_IDENTIFIER")primaryKey("BOOK_ID", "INSTRUMENT_ID", "COUNTERPARTY_ID").name("POSITION_BY_BOOK_INST_CPTY)

indices

Indices are typically specified for one of two reasons:

- to add unique value constraints on records in the table, in addition to the primary key

- to add a more efficient way to look up ranges of records for the table

Fields marked as part of any index must not be null.

As with primary keys, index names are auto-generated. If you wish to give your index a specific name, apply .name(<pk name>) against it.

There are two types of index:

unique

Unique indices are the same as a primary key, in that any combination of values for fields defined in the index must uniquely identify a record.

A unique index can be defined by:

- adding

.uniqueIndex()to a field (single field unique indices only) - adding

unique(<field 1>, <field 2>, ...)to theindicesblock of a table.

As with multi-field primary keys, the order in which the fields are specified should be considered.

nonUnique

Non-unique indices are used to ensure efficient ranged lookup of records, and there are no constraints around record value uniqueness as seen with primary keys and unique indices.

An example usage would be if you had a POSITION table which had a non-unique index set on COUNTERPARTY_ID, it allows for efficient lookups of all POSITION records for a given COUNTERPARTY_ID

A non-unique index can be defined by:

- adding

.nonUniqueIndex()to a field definition (single field non-unique indices only) - adding

nonUnique(<field 1>, <field 2>, ...)to theindicesblock of a table.

As with multi-field primary keys, the order in which the fields are specified should be considered.

Field-level index definition vs indices block-level definition

Here are two different ways of defining a non-unique index. Both are equally valid.

//Field level

table(name = "POSITION", id = 11003) {

...

field("COUNTERPARTY_ID", LONG).nonUniqueIndex()

...

}

//Indices block

table(name = "POSITION", id = 11003) {

...

field("COUNTERPARTY_ID", LONG)

...

indices {

nonUnique("COUNTERPARTY_ID")

}

}

subTables

Within the body of the table definition, you can use subtables to define one or more subtables. A subtable is related to the parent, in that it shares any fields defined in the parent's key.

For example, you might have an EXECUTION_VENUE table to provide details of different exchanges and trading venues. There might be alternative codes used to identify this exchange, and we need a table to represent a set of codes for each venue ID. So, you could add a subtable called ALT_VENUE_CODE, in which the relationship is one-to-many from the parent.

The example below shows this. After the fields and the primary key have been defined, you can see the subtable ALT_VENUE_CODE.

- The

EXECUTION_VENUE_IDfield is used to generate the join operation. This field is inherited automatically. - Then the additional fields

ALT_VENUE_CODEandALT_VENUE_CODE_TYPEare defined. - Then the key for the subtable is defined, and includes the

EXECUTION_VENUE_ID

table(name = "EXECUTION_VENUE", id = 5043) {

field(COUNTRY_CODE)

field(OPERATING_MIC)

field(DESCRIPTION)

field(EXECUTION_VENUE_ID)

primaryKey("EXECUTION_VENUE_ID")

subTables {

fields("EXECUTION_VENUE_ID")

.joiningNewTable(name = "ALT_VENUE_CODE", id = 5044) {

field("ALT_VENUE_CODE")

field("ALT_VENUE_CODE_TYPE")

primaryKey("EXECUTION_VENUE_ID", "ALT_VENUE_CODE_TYPE")

}

}

}

Some of the tables provided as standard by the Genesis Server Framework use this method. The example below shows the GENESIS_PROCESS monitoring table, which holds a record per application process. This table has a subtable called GENESIS_PROCESS_MONITOR defined, which records the state of the process on each given host in the application cluster.

table(name = "GENESIS_PROCESS", id = 12) {

field(PROCESS_NAME)

field(PROCESS_HOSTNAME)

...

primaryKey("PROCESS_NAME", "PROCESS_HOSTNAME")

subTables {

fields("PROCESS_HOSTNAME", "PROCESS_NAME")

.joiningNewTable(name = "GENESIS_PROCESS_MONITOR", id = 20) {

field("MONITOR_NAME")

field("MONITOR_MESSAGE", STRING(4_000))

field("MONITOR_STATE", ENUM("GOOD", "BAD"))

primaryKey("PROCESS_HOSTNAME", "PROCESS_NAME", "MONITOR_NAME")

}

}

}

view

Views are defined in *-views-dictionary.kts files. These must be placed in the cfg folder in your application's server codebase. They enable you to create views of the data, which draw their data from more than one table.

| Parameter name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

name | String | Name of the view, must be unique across the application |

table | String | Root table of the view |

Updates to the root table (table ) of the view will always trigger updates for any subscribing clients.

joins

A join creates a relationship between a field (or fields) in the root table and a field (or fields) in another table. To define a join, use the joins block.

Each join must start with joining(<table to join to>). It must then list each field in the root table, along with the field you want to join to in the other table. Here is a simple example that joins the INSTRUMENT_ID field in the root table (TRADE) to the INSTRUMENT_ID field in the INSTRUMENT table.

views {

view("TRADE_VIEW", TRADE) {

joins {

joining(INSTRUMENT) {

on(TRADE.INSTRUMENT_ID to INSTRUMENT { INSTRUMENT_ID })

}

}

...

}

}

In the example above, a record is displayed in the view if the INSTRUMENT_ID in the TRADE table matches the INSTRUMENT_ID in the INSTRUMENT table.

If more than one field is needed to create the relationship, add a .and() to the on(). For example:

joining(POSITION) {

on(TRADE.BOOK_ID to POSITION { BOOK_ID })

.and(TRADE.INSTRUMENT_ID to POSITION { INSTRUMENT_ID })

}

In the example above, a record is displayed in the view only if:

- INSTRUMENT_ID in the TRADE table matches INSTRUMENT_ID in the POSITION table

AND - BOOK_ID in the TRADE table matches BOOK_ID in the POSITION table

You can also add nested joins, joining to joined tables, recursively as needed, by adding an inner .joining statement:

joining(INSTRUMENT) {

on(TRADE.INSTRUMENT_ID to INSTRUMENT { INSTRUMENT_ID })

.joining(ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID) {

on(INSTRUMENT_ID.INSTRUMENT_ID to ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID { INSTRUMENT_ID })

.and(ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID { ALTERNATE_TYPE } to "REFINITIV")

}

}

The above example also demonstrates how to use a hard-coded value to join. Note where ALTERNATE_TYPE is set to "REFINITIV".

Joins can be one-to-one (key field match) or one-to-many (part-key-field match). However, Views with one-to-many joins cannot be used to power real-time queries - as they would be very inefficient and could potentially use up a lot of the cache.

backwardsJoin

Joins can be set as backwards joins, using backwardsJoin = true in the joining definition.

By default, only updates to the root table are published in real time to subscribers to the view. To include real-time updates to the joined tables as well, you need to create a backwards join.

For example, if our root TRADE table joins to INSTRUMENT, and it's a backwards join, an update to an INSTRUMENT record will trigger real-time updates to connected clients for all rows which join to the updated INSTRUMENT record.

views {

view("TRADE_VIEW", TRADE) {

joins {

joining(INSTRUMENT, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(TRADE.INSTRUMENT_ID to INSTRUMENT { INSTRUMENT_ID })

}

}

...

}

}

There is a memory storage and processing overhead when a join is defined as a backwards join. In very large datasets, this can be significant.

Only specify a backwards join where it is essential to publish updates to the joined table in real time.

joinType

Available join types are JoinType.INNER and JoinType.OUTER.

INNERjoins require all joins to match exactly; if one single join fails to match, the row will be discarded.OUTERjoins provide null references for failed joins and will still allow the row to be built.

If you do not specify the joinType, it defaults to JoinType.OUTER.

joining(INSTRUMENT, JoinType.INNER) {

on(TRADE { INSTRUMENT_ID } to INSTRUMENT { INSTRUMENT_ID })

Parameterized joins

Some join operations require external parameters that are not available in the context of the table-join definition, but which will be available when the view repository is accessed (e.g. client-enriched definitions), so an option exists to create parameterized joins.

These are typically used in Request Server queries:

view("INSTRUMENT_PARAMETERS", INSTRUMENT) {

joins {

joining(ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID, JoinType.INNER) {

on(INSTRUMENT.ID to ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID.INSTRUMENT_ID)

.and(ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID.ALTERNATE_TYPE.asParameter())

}

}

fields {

ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID {

ALTERNATE_CODE withAlias "INSTRUMENT_CODE"

}

INSTRUMENT {

NAME withPrefix INSTRUMENT

}

}

}

So for the above, if we had a Request Server using the view, it would make ALTERNATE_TYPE available as a field input parameter.

Dynamic joins

Dynamic joins have a shared syntax with derived fields. However, rather than specifying a field name and type, the view should always return an entity index type of the table you’re joining on.

When using dynamic joins on aliased tables, the alias name should match the alias variable name. E.g.: val fixCal = TRADE_CALENDAR withAlias "fixCal"; here it is fixCal in both cases.

As with derived fields, you can use the withEntity and the withInput syntax. However, the lambda should always return an entity index object or null. Also, it should always return the same type. It is not possible to switch dynamically between indices, so it should always return the same type or null. It is possible to add further and clauses afterwards.

Syntax:

joining({usual join syntax}) {

on {

// either

withEntity({table name}) {

// build index entity here

}

// or

withInput({field 1}, {field 2}, .., {field 9}) { a, b, .. ->

// build index entity here

}

}

}

Example usage

Before:

joining(fix, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(TRADE_TO_SIDE { FIX_ID } to fix { SIDE_ID })

.and(fix { SIDE_TYPE } to SideType.FIX)

.joining(fixCal, JoinType.INNER, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(fix { CALENDAR_ID } to fixCal { CALENDAR_ID })

}

}

After:

joining(fix, backwardsJoin = true) {

on {

withEntity(TRADE_TO_SIDE) { tradeToSide ->

TradeSide.BySideId(tradeToSide.fixId)

}

}

.and(fix { SIDE_TYPE } to SideType.FIX)

.joining(fixCal, JoinType.INNER, backwardsJoin = true)

}

Before:

joining(fixCal, JoinType.INNER, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(fix { CALENDAR_ID } to fixCal { CALENDAR_ID })

}

After:

.joining(fixCal, JoinType.INNER, backwardsJoin = true) {

on {

withInput(fix { CALENDAR_ID }) { calendarId ->

when (calendarId) {

null -> null

else -> TradeCalendar.ByCalendarId(calendarId)

}

}

}

}

Multiple joins on the same table

To be able to perform multiple joins on the same table, you need to use one or more aliases:

val firm = BID_OFFER withAlias "firm"

val draft = BID_OFFER withAlias "draft"

joins {

joining(firm, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(firm { BID_STATE } to BidState.FIRM)

}

joining(draft, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(draft { BID_STATE } to BidState.DRAFT)

}

}

fields {

firm {

BID_PRC withAlias "FIRM_BID_PRC

}

draft {

BID_PRC withAlias "DRAFT_BID_PRC"

}

}

fields

The fields block allows you to define which fields you would like to include in your view. You can reference fields from any of the tables that have been joined inside your view.

Adding a field is as simple as typing it in the fields section of the view.

fields {

INSTRUMENT.CURRENCY_ID

}

You can add all the fields from a given table to a view using the allFields accessor.

fields {

TRADE.allFields()

}

If a field has the same name as the field name in another table in the view, you can use one of the following operators to override the field name:

withAliasgives the field an alternative name on the viewwithPrefixadds a prefix to the standard field name; this is useful if you have a clash

For example, if you have COUNTERPARTY joined to INSTRUMENT and both have a NAME field:

COUNTERPARTY.NAME withPrefix COUNTERPARTY

INSTRUMENT.NAME withPrefix INSTRUMENT

INSTRUMENT.CURRENCY_ID withAlias "CURRENCY"

derivedField

Derived fields are used to serve up data that is constructed from one or more fields; this is modified programmatically before progressing.

For example, if a TRADE table has a PRICE and a QUANTITY field, you can define a derived field NOTIONAL as the product of the two.

There are two ways of defining a derived field:

- Using

withInputenables you to specify one more more fields as the basis for calculating the value of the new derived field. - Using

withEntityenables you to specify a table entity as the input and refer to any of its fields. If you are using multiple fields from the same table to create your derived field, it is easier to use this method. You can reference any field in the specified table (entity) to create your derived field. This is easier than providing all the fields you want as separate parameters.

Using withInput

derivedField("NOTIONAL", DOUBLE) {

withInput(TRADE.PRICE, TRADE.QUANTITY) { price, quantity ->

price * quantity

}

}

The maximum number of fields that can be used as input of a derived field is 10.

Using withEntity

derivedField("NOTIONAL", DOUBLE) {

withEntity(TRADE) { trade ->

trade.price * trade.quantity

}

}

By default, all fields in the entity are returned. So there could be a performance impact if you are using large tables; it is likely that your calculations won't need many of the fields that are loaded in your calculation or in the final view.

There two options which could mitigate this.

The first way is to return only non-null fields. Here is an example:

derivedField("SPREAD", DOUBLE) {

withEntity(INSTRUMENT_PRICES, onlyNonNullFields = true) { price ->

price.askPrice - price.bidPrice

}

}

The second way is to specify the fields to be returned. Other fields in the table are not returned. Here is an example:

derivedField("SPREAD", DOUBLE) {

withEntity(INSTRUMENT_PRICES, fields = listOf(INSTRUMENT_PRICES.ASK_PRICE, INSTRUMENT_PRICES.BID_PRICE)) { price ->

price.askPrice - price.bidPrice

}

}

Example view with more complex derived fields

view("POSITION_VIEW", POSITION) {

joins {

joining(ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(POSITION.INSTRUMENT_ID to ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID { INSTRUMENT_ID })

.and(ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID { ALTERNATE_TYPE } to "REFINITIV")

.joining(INSTRUMENT_L1_PRICE, backwardsJoin = true) {

on(ALT_INSTRUMENT_ID.INSTRUMENT_CODE to INSTRUMENT_L1_PRICE { INSTRUMENT_CODE })

}

}

joining(INSTRUMENT) {

on(POSITION.INSTRUMENT_ID to INSTRUMENT { INSTRUMENT_ID })

}

}

fields {

POSITION.allFields()

INSTRUMENT.NAME withPrefix INSTRUMENT

INSTRUMENT.CURRENCY_ID withAlias "CURRENCY"

derivedField("VALUE", DOUBLE) {

withInput(

POSITION.QUANTITY,

INSTRUMENT_L1_PRICE.EMS_BID_PRICE,

INSTRUMENT_L1_PRICE.EMS_ASK_PRICE

) { quantity, bid, ask ->

val quant = quantity ?: 0

//Use BID if positive position, else ask if negative

val price = when {

quant > 0 -> bid ?: 0.0

quant < 0 -> ask ?: 0.0

else -> 0.0

}

price * 1000 * quant

}

}

derivedField("PNL", DOUBLE) {

withInput(

POSITION.QUANTITY,

POSITION.NOTIONAL,

INSTRUMENT_L1_PRICE.EMS_BID_PRICE,

INSTRUMENT_L1_PRICE.EMS_ASK_PRICE

) { quantity, notional, bid, ask ->

val quant = quantity ?: 0

//Use BID if positive position, else ask if negative

val price = when {

quant > 0 -> bid ?: 0.0

quant < 0 -> ask ?: 0.0

else -> 0.0

}

val marketVal = price * 1000 * quant

marketVal - notional

}

}

}

}

}

Migrating from legacy data model structure

Before version 7.2 of the Genesis Platform fields were defined in their own dictionary file, separately from tables.

From version 7.2, Genesis supports the new syntax detailed in this document.

In *-tables-dictionary.kts files we went from this...

table(name = "RIGHT", id = 1004) {

CODE

DESCRIPTION

primaryKey {

CODE

}

}

...to this:

table(name = "RIGHT", id = 1004) {

field("CODE").primaryKey()

field("DESCRIPTION")

}

Legacy will continue to work, but it is simple to move to the new model using a provided a gradle plugin.

To start, add the following line to the top of the build.gradle.kts file for the module which contains your legacy dictionary files:

plugins {

id("global.genesis.dictionary.upgrade")

}

After adding this and performing a Gradle refresh, a new task: updateTablesDictionary is available in the Gradle task list, under genesis.

To migrate the table dictionaries in your config module, run the task.